The challenge: skilled women, broken markets

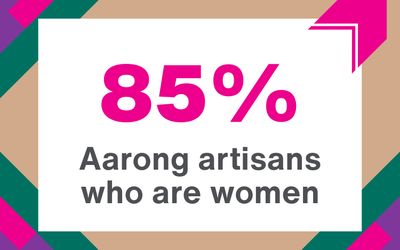

For millions of women living in situations of extreme poverty around the world, having skills is not enough. A woman may be a talented artisan, farmer, or producer. She may know how to weave, sew, embroider, raise livestock, or grow vegetables.

But without fair access to markets, her work may go unpurchased. She might earn pennies for long hours of labour. Middlemen may take large cuts. Orders may be unreliable, and payment may be late. Her potential may go unfulfilled.

Without steady income, her family may struggle to afford food, health care, or education. Even the hardest workers can remain stuck in the poverty trap - not because they lack ability, but because the system is stacked against them.

This is one of the challenges BRAC set out to solve decades ago: How do you create lasting income for women? How do you build a system where they are fairly paid? How do you multiply a woman’s power - not just once, but for good?

The solution: reinvent the market and put people first

BRAC developed its social enterprise model to do what traditional markets often fail to do: put people first. “Financial viability is very important,” notes Tamara Hasan Abed, Managing Director of BRAC’s Social Enterprises. “But the whole purpose of a social enterprise is to solve a social problem.”

People living in rural areas - especially women - often face the highest barriers to overcoming poverty. Distance from larger urban markets and a lack of distribution systems can block opportunity. Without access to consumers in a broader market, they may struggle to find demand for their products.

Our approach addresses that. By building platforms, expanding access, and creating new systems from the ground up, we connect rural producers directly to national markets. With a reinvented market, women can earn a steady income and plan for the future.

Tamara explains, “The fortune is at the bottom of the pyramid. We at BRAC don’t look to people at the bottom of the pyramid as consumers for our products, but rather as producers - whether they’re farmers or producing other goods. We look at how people can create sustainable livelihoods, ones their families can grow and depend on.”

The impact for artisans: from irregular wages to reliable income

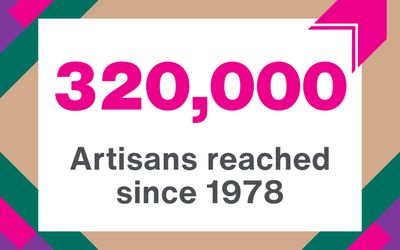

Founded in Bangladesh in 1978, Aarong was created to connect women in rural areas to consumers in urban markets. At the time, artisans often waited weeks or months for their earnings from urban retailers. Aarong allowed them to sell their fashion and homeware products at a fair price and receive consistent orders.

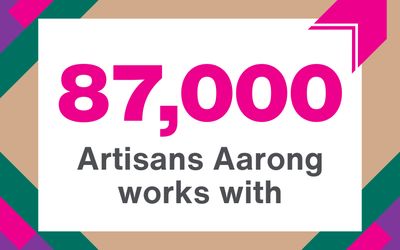

What began as a small initiative has grown into one of the country’s largest social enterprises and a leading fair-trade fashion and lifestyle brand. Today, Aarong works with tens of thousands of craftspeople. They create textiles, jewellery, leatherwork, pottery, baskets, woodcrafts, and more. Aarong operates 31 retail stores (including the world’s largest craft store!) and ships globally.

Aarong also preserves traditional folk art and craft techniques while adapting them for modern markets. Otherwise, crafts passed down through generations, such as handwoven Jamdani and hand-stitched nakshi kantha could disappear.

Artisans can access free training to develop skills through an apprenticeship model. They can also get holistic support for their whole family, including health care, microfinance, and savings services. If they have children, they can enrol them in a BRAC school. Senior workers get retirement benefits, too

The model pays off. “Aarong now has annual revenue of about $150 million, and we invest 50% of our surplus into BRAC’s development work,” Tamara says. Revenue is reinvested to help sustain programmes, critical in this era of disappearing foreign aid.

That’s what makes social enterprises so effective; they don’t depend solely on donations to function. Instead, they create self-sustaining systems that grow year after year.

The impact for dairy farmers: from low prices to reliable income

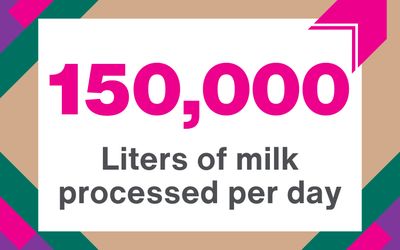

BRAC Dairy, also known as Aarong Dairy, is Bangladesh’s largest dairy brand. It was created in 1998 to address the challenges faced by farmers who took out loans to purchase cows. The animals produced high-quality milk, but the lack of refrigerated storage facilities meant farmers were forced to sell milk at any price they could get.

We built collection centres and chilling facilities to give farmers the chance to sell surplus milk for a fair price. Now, milk is collected through centres in rural areas. It is processed centrally into drinking milk, yoghurt, and butter and sold nationwide.

It ensures fair prices for thousands of farmers and makes high-quality milk more accessible. As a result, national nutrition has improved.

For many dairy farmers, many of whom are women, this is the first reliable income they’ve ever received. With a steady wage, their children are more likely to stay in school. Their whole family’s nutrition improves. They can plan for emergencies. Health care becomes possible.

The big picture: redesigning markets to erase poverty

Instead of encouraging women to fit into markets that don’t serve them, BRAC redesigned those markets. The result? Multi-million-dollar brands and proof that you don’t need to choose between profit and purpose. You can have both.

But the need is still great. Millions of women around the world are ready to work. But they don’t have access to consumers, capital, or systems that recognize their value. And as funding for development continues to decrease, there’s even more potential to eliminate poverty through social enterprise.